BILL EVANS: TIME REMEMBERED

After pianist Bruno Heinen and electric guitarist Kristian Borring issued Postcard To Bill Evans in fall of 2015, I attempted to make a mental tally of all the album-length tributes to Evans that have appeared since his death at fifty-one in 1980. It turns out that they're plentiful in number, with ones by the Kronos Quartet (Music of Bill Evans, 1986), John McLaughlin (Time Remembered: John McLaughlin Plays Bill Evans, 1993), and Eliane Elias (Something for You - Eliane Elias Sings and Plays Bill Evans, 2008) some of the more noteworthy (it's hardly insignificant that not just pianists but a string quartet and guitarist have paid homage). Only the most distinguished of artists is memorialized in such a manner, which puts Evans, born in Plainsfield, New Jersey on August 18, 1929, in the esteemed company of fellow greats Ellington, Mingus, Monk, and Holiday.

Speaking of which, while stylistically it would be hard to imagine two players seemingly more unlike than Monk and Evans, they do clearly share one thing: as much as their own compositions have become standards, the two also had an especial gift for breathing new life into standards and show-tunes, whether it be “Someday My Prince Will Come” (from Disney's 1937 animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) in Evans' case or “Just a Gigolo” in Monk's. Regardless of whatever stylistic gulf separates them, Evans cited Monk as one of his favourite pianists and also held Erroll Garner and Nat King Cole in high regard.

Thelonious Monk, Erroll Garner, and Nat King Cole

Heinen shares with Evans key traits, among them delicacy of touch, elegant phrasemaking, and a penchant for lyricism, and like Evans he also deftly blends the refinement of classical technique with the fundamental swing of jazz. Heinen has openly acknowledged Evans as his number one influence, which isn't all that surprising yet in another sense is, given the huge number of jazz pianists he might conceivably have cited in Evans' place. That and a number of other things got me wondering what specifically it is about him that accounts for his staying power and broad influence thirty-six years after his death. To answer such a question, I revisited my own Evans catalogue and also contacted a number of artists who either played with or were influenced by him. Reflections by Heinen, Evans bassists Chuck Israels and Marc Johnson, Jack DeJohnette, and Bill Frisell will help bring the picture into sharper focus, but first some preparatory background is in order.

Evans' Music

He issued a voluminous number of recordings, but one release in particular can't help but stand out: The Complete Riverside Recordings. Yes, there are other box sets for other periods, but in featuring 147 tracks (some alternate takes), the Riverside one is indispensable, especially when it includes two of Evans' most celebrated recordings, Sunday at the Village Vanguard and Waltz For Debby, both from 1961 and featuring the pianist with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian (ten days after the June 25, 1961 live date from which the albums' content was drawn, LaFaro died in a highway accident). The highlights on the box set are too numerous to mention; the agile to-and-fro between the pianist and bassist on “Autumn Leaves” is surely one, and the live renderings of LaFaro's “Gloria's Step” and “Jade Visions” are memorable, too. The Riverside collection also concludes with Evans performing with Israels and Larry Bunker at Shelly's Manne-Hole in Hollywood on May 30-31, 1963. The box set's notable for including a multitude of covers but also many of Evans' own greatest pieces, among them: “Waltz For Debby,” “Re: Person I Knew,” “Peri's Scope,” “Five,” “Peace Piece,” “Very Early,” “Show-Type Tune,” “Time Remembered,” and “Blue in Green,” the latter co-credited to Miles Davis but thought by many to be solely written by Evans.

Scott LaFaro, Evans, and Paul Motian at the Village Vanguard in 1961

Obviously many post-Riverside albums are terrific, too, among them: Bill Evans at Town Hall, the 1967 release featuring Israels and drummer Arnold Wise (the bassist's last recorded appearance as a regular member of the Bill Evans Trio); 1968's Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival with Eddie Gomez and DeJohnette (the only album Evans made with the drummer); and 1983's The Paris Concerts, Editions One and Two (the performance itself having occurred on November 26, 1979) with Johnson and Joe LaBarbera in the final iteration of the Bill Evans Trio. Also worth a mention is 1975's The Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album (the two would reconvene two years later for Together Again), which includes a lovely rendition of “Some Other Time” (from the musical On the Town, with music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green).

John Coltrane, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, Miles Davis, and Evans during the Kind of Blue sessions

Of course many listeners were first introduced to Evans by way of Kind of Blue; though the pianist's 1958-59 tenure with Miles was brief, Evans' playing on the album is certainly one of the reasons accounting for its impact. Still, his time with the trumpeter constitutes but one episode in a life rich in incident both before and after, and no account of Evans would be complete without an overview, however brief, of his life.

Evans' Life

Classically trained, he studied at Southeastern Louisiana University, a background that helped bring an uncommon elegance to his playing. His exposure to classical music occurred long before his post-secondary years, and his familiarity with the works of Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Stravinsky, Khachaturian, Gershwin, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, and Debussy is evident in the sophistication Evans brought to even the simplest standard. That exposure contributed to his refined touch at the piano and helped set him apart from fellow pianists with no such grounding. (It bears worth mentioning that while his piano studies began at the age of six, he also received instruction in violin when he was seven and flute at thirteen.)

His at times boppish debut album New Jazz Conceptions, produced by Orrin Keepnews (whom Evans would later honour with the anagrammed title “Re: Person I Knew”) and featuring Evans in the company of Motian and bassist Teddy Kotik, included “Waltz For Debby” (which he'd composed for his young niece in 1953) in a short solo piano form. The 1956 album inaugurated a productive relationship with Riverside that would last many years; the triple meter and lilting flow of the song itself set it apart and helped make it become his one of his most beloved compositions.

The album follow-up, Everybody Digs Bill Evans, featuring bassist Sam Jones and drummer Philly Joe Jones (a recurring favourite of the pianist's), appeared in 1959; a year later, Portrait in Jazz was released, the first album to pair Evans with LaFaro and Motian. Though Evans wasn't averse to playing in ensemble settings, solo and trio playing dominates his recorded oeuvre, the most innovative example of the former the 1963 recording Conversations with Myself, which features Evans anticipating by many years the now-commonplace technique of overdubbing (issued on Verve, the album also brought Evans his first Grammy award; in a similar solo vein, 1968's Alone brought him his third).

Evans, Chuck Israels, and Larry Bunker performing "Waltz For Debby"

Each trio left a lasting mark, yet it was the one featuring LaFaro and Motian that's today regarded as the most indelible. Following LaFaro's tragic death, Evans re-emerged with Israels as LaFaro's excellent replacement (Israels' first recordings with Evans and Motian in 1962 were issued under the album titles Moonbeams and How My Heart Sings) and with the later addition of Bunker the second Bill Evans trio formally came into being. In 1966, Evans was joined by bassist Eddie Gomez, whose tenure with the pianist would last for eleven years, and two years later drummer Marty Morell and eventually Eliot Zigmund; other combinations followed until Johnson and LaBarbera joined the pianist for his final trio. (Naturally, a large number of other musicians also played with Evans, Lee Konitz, Zoot Sims, Jim Hall, Toots Thielemans, Ron Carter, Percy Heath, Stan Getz, Paul Chambers, and Freddie Hubbard among them.)

Admittedly no account of Evans is complete without mentioning the part drugs played in his life; his heroin and later cocaine use, coupled with a life-long bout with hepatitis, certainly contributed to his early demise. His heroin addiction began in the late ‘50s and reared its head off and on for many years, and though he did manage to abstain for a decade, during the late ‘70s a cocaine addiction set in. Such long-term self-abuse no doubt hastened his early death on September 15, 1980 at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.

Evans' Style

The bespectacled Evans cut a distinctive figure, and he was by most accounts shy, introspective, modest, and intellectually curious. But though he was undeniably intelligent, he marshaled his intellectual energies in the service of emotional effect; for him, feeling trumped everything. Some musicians feed off an audience's energy; Evans, on the contrary, appeared so deeply immersed in his playing that the presence of anyone outside him seemed moot, though he clearly wasn't unresponsive to those with whom he was playing and the audience. Seeing him hunched over the keyboard, one might have felt as if one were eavesdropping on someone involved in something deeply private.

In fact, the silhouette of Evans engaged in telepathic communion with the piano has become one of the signature images of jazz, as indelible as the one of Miles Davis. That posture was not mere affectation either, but rather a physical stance that enabled his hands to rest on the keys at an angle that would provide optimal pressure control. Refining the nuance of touch further, Evans' left hand would play the chords softly in order to allow the right hand's melody to resonate clearly. Peter Pettinger describes the pianist's playing as follows: “The whole moved as a loping unit, a unified concept in which the harmonic cushion was harnessed to the rhythmic contour of the top line” (Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings, Yale University Press, 1998, New York, New York, p. 106) and elsewhere nicely articulates another distinguishing aspect of his playing: “He seemed incapable of anything indiscriminate or inconsequential, even when comping” (p. 48). The graceful flow of his playing, the finely calibrated balance between the left and right hands, the nuanced touch—all such qualities are integral to Evans' sound.

As celebrated a figure as he is, he wasn't without an occasional detractor. Of Trio '65, reviewer John S. Wilson wrote, “The more I hear of Evans, the more I become convinced that the propagation of the Evans mystique must be one of the major con jobs of recent years ... This is great jazz? It's more like superior background music, music that forms a pleasant atmospheric setting but does not distract” (Down Beat, July 15, 1965, p. 32). Appreciation for Evans' artistry is in far greater supply, however, and has grown immeasurably over the years. He was honoured numerous times in Down Beat's polls by readers and critics alike, was elected into the magazine's “Hall of Fame” in 1981, and in addition to being the recipient of multiple Grammy Awards, was posthumously honoured with the “Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award” in 1994.

Other Artists' Reflections

The impressions of Evans by those who either played with him or were influenced by him later help crystallize what it is about the pianist that sets him apart. We begin with contemporary pianist Bruno Heinen.

Bruno Heinen

“My favourite Bill tune has to be ‘Time Remembered,' not only my favourite piece by him, but my favourite composition of any composer,” says Heinen (personal communication, March 18, 2016). “As the title suggests, it speaks to me of nostalgia and expanding time. The absence of any dominant chords gives it a serene impressionistic gracefulness, and the snaking melody weaves around the changes in the most subtle yet unexpected way; the unusual form of twenty-six bars also adds another dimension of rolling time. Apart from anything else, the changes are beautifully constructed, making it great fun to play. For me this is the perfect crystallization of a standard that sounds anything but.”

Musing on Evans' enduring influence, Heinen states, “He was my way into jazz. As a classical musician, he spoke to me first with the beauty of his touch at the piano. His strength of ideas, innovations in trio playing, and original compositions are all reasons for his lasting influence, in my opinion. The biggest factor for me, however, is his communication with the listener; his music and playing have the perfect combination of being intellectual yet accessible. His trio with LaFaro and Motian made some of my favourite music of all time; their synergy and communication within the trio changed the way I thought about music. He will remain my biggest influence.”

Jack DeJohnette

Asked to choose a favourite Evans composition, DeJohnette (personal communication, February 7, 2016), who, as mentioned, appears on Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival and played with the pianist before joining Miles's Live-Evil outfit, selects “Peace Piece”: “I like this composition because it reminds me of Erik Satie's Gymnopédies series. Bill's playing is warm and reflective on this, and I'm also a big fan of Satie.” Though Evans recorded it as an improvisation, “Peace Piece” grew out of “Some Other Time” but in an unusual way. According to Orrin Keepnews, Evans was working on an ostinato-based introduction to Bernstein's show-tune when he suddenly decided to use what he'd created as an independent piece, and though it is not based on the chords of the song, it does play like an extension of it (“The Bill Evans Sessions,” booklet accompanying The Complete Riverside Recordings, Riverside, 1984). DeJohnette accounts for Evans' influence in succinct but no less astute terms by highlighting “his melodic and harmonic approach, and the romanticism in his playing and his compositions.”

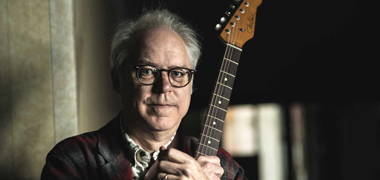

Bill Frisell

“What makes it difficult to choose a single Evans composition is that's it's so hard to separate his own pieces from the covers he did,” says the guitarist (personal conversation, February 15, 2016). “His version of Gershwin's ‘My Man's Gone Now' is a piece that's always been so important to me; it was the song that first turned me on to him and is one I constantly come back to. Even though it's not an original Evans composition, he put his stamp on it so strongly. It also was one of the first things of his I heard in high school, at a time when I was just starting to discover this incredible world of music and people like Jim Hall and Bill.

“In fact, we played the song during my very first rehearsal with Paul Motian. In 1981 I got a call out of the blue from Paul, which turned out to be probably the most important phone call of my life, to go to his apartment, and when I got there I met Paul and Marc Johnson for the first time. Bill had passed away not all that long ago, maybe about a year, and here I was playing guitar in the company of Paul and Marc, both of who had played with Bill for so many years, and the first song we played was ‘My Man's Gone Now.'” (Frisell would go on to play with Motian for many years in various group settings and also was an integral part of Johnson's Bass Desires outfit, with John Scofield and Peter Erskine the other members; Frisell also plays on Motian's 1990 Bill Evans set alongside Johnson and Joe Lovano.)

But though Frisell didn't play with Evans, he did meet him. “That happened around 1971-72 when I was living in Denver, Colorado where his trio with Eddie Gomez and Marty Morell was playing in a little club for a week. At the time Bill was like a god to me, so my musician friends and I went every night for the entire week,” the guitarist recalls. “Listening to Bill play was like a religious experience, and he was such an inspiration; he made me feel that if I were to keep practicing, maybe I could reach a similar kind of level. At the end of one of those gigs, about one in the morning, we were leaving the club to drive home when we saw Bill standing in the middle of the street, all alone, looking like he was stranded. So we went up to him, nervously introduced ourselves, and eventually gave him a ride to his hotel. I'll never forget him telling us how dissatisfied he was with what he'd been playing, whereas I, on the other hand, felt as if what I'd been hearing was the most beautiful, transcendent thing I'd ever heard. It was such an epiphany to discover that his own take on his playing differed so dramatically from my own impression of it.”

When asked to explain Evans' continuing influence, Frisell replies, “There are so many things that could be cited—how incredibly deep it is, how layered it is, but there's also the humility and honesty of his playing. He really set the bar for what we aspire to as musicians.”

Marc Johnson

Not only was Johnson interested in playing with Evans when the opportunity presented itself in 1978, the twenty-four-year-old bassist brought a classical background (North Texas State University, specifically) to the gig. With drummer LaBarbera aboard, the final Bill Evans Trio began playing together in January 1979. In the years following Evans' death, Johnson has issued a number of exceptional recordings, among them the two Bass Desires releases, the self-titled debut in 1985 and Second Sight two years later, and The Sound of Summer Running, a 1998 set featuring Frisell, Pat Metheny, and Joey Baron.

When asked to pick a favourite Evans composition, Johnson replies (personal communication, February 27, 2016), “I can't say that I have one; there are several for me that have a special significance. One would be ‘Re: Person I Knew' because of the way the harmony moves over a pedal point, and it was the tune we played every night to open the first set. It is a gentle, introspective piece that creates an atmosphere of quietude and in some subtle way suggests to the audience that to hear this music, one should be still to listen. Another would be ‘34 Skidoo' because of the energy implicit in the performance and the structure of basically two alternating sections. The first is in 4/4 over an E pedal point, the second in 3/4 over a chord sequence that takes you to the next 4/4 section over a C pedal point, which gives way to the last section now in 3/4 using a chord sequence to arrive back at the top of the form to the E pedal again. The way Bill approaches the melodic improvisations, you feel the implication of 3/4 time during the 4/4 sections and the implication of 4/4 time in the 3/4 sections. So the overall effect is very intense as the structure sets up these parallel tension and resolution systems, in the harmony and in the time signatures.

“Bill revealed an incredible depth of emotion in his music. Gene Lees wrote that Bill's music had a way of revealing to people emotions that they didn't know they had,” he continues. “Bill's music is, above all, very clear. Because of this, I believe his music is more understandable and approachable by young musicians and listeners on many levels. One thing jazz listeners recognize when they compare artists from one to another is that Bill truly created his own musical universe. He had his early influences to be sure, but you can hear Bill's striking uniqueness as a jazz artist through the sound he produced from the piano to the development of clear and logical voice leading and ways of voicing chords, to his way of displacing harmonic rhythm and finding freedom in a very personal melodic/improvisatory language that expresses the melodic line in myriad shapes and permutations through harmony.”

Chuck Israels

It's only fitting that the final word should go to Israels, someone eminently qualified to pronounce on Evans' artistry. The pianist first heard Israels as a student playing bass at Brandeis University in 1955. After graduating, he played in Europe with Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke and upon returning to the US played in George Russell's sextet (Pettinger, p. 120). Having become acquainted with Israels' playing style, Evans regarded him as the natural successor to LaFaro, and sure enough the call eventually came. How fine a replacement Israels was for his innovative predecessor is shown in the video for “My Foolish Heart,” which captures Evans' ability to transmute popular song material into something reverential.

Asked to choose a single Evans piece, Israels replies (personal communication, February 10, 2016), “Hard to answer that question—there are different compositions for different characters and moods. ‘Waltz for Debby,' ‘Walkin' Up,' ‘Turn Out The Stars,' ‘Peri's Scope,' ‘Five,' ‘Blue in Green'—all are wonderful and individual statements.”

On the subject of Evans' enduring influence, Israels says, “The same things that make all good art endure: a balanced aesthetic system that omits nothing, a system that is informed by a profound understanding of, and commitment to, the history of great music; simplicity and complexity; conflict and resolution (harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic); dynamic and textural nuances; a sensitive use of the poetry of simple (but not simple-minded) folk and popular music; density and space, integral motivic development; dramatic contrast. In short, there's nothing left out, it's all there, and Bill would have just said ‘truth and beauty.' Easy to say, hard to achieve.”

textura is deeply grateful to Jack DeJohnette, Bill Frisell, Bruno Heinen, Chuck Israels, and Marc Johnson for their invaluable contributions to this article.

April 2016

![]()