FIVE QUESTIONS WITH MARK JOHN MCENCROE

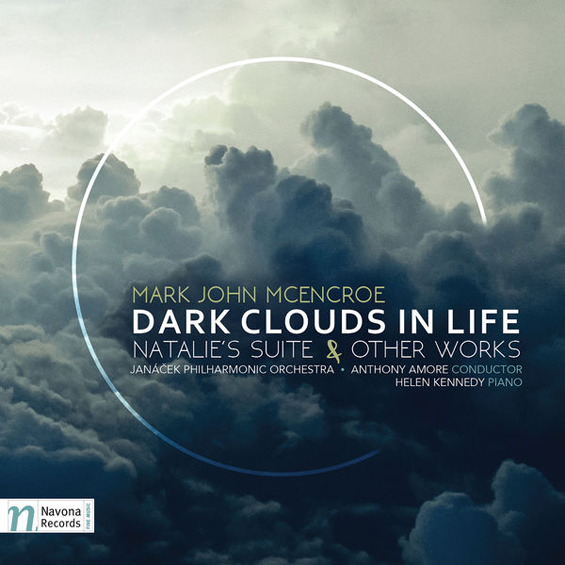

To say that Mark John McEncroe has led a life unlike any other composer hardly does the claim justice; after all, how many others can say they came to a career in music after working as both a chef and label manager, as he did. Luckily for us, the Sydney, Australia-born artist eventually did turn his attention to composing, a move that has resulted in a number of piano and orchestral works and recordings, specifically two piano releases, Reflections & Recollections Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, and two orchestral recordings, Affirmations & Aspirations and Dark Clouds In Life (upcoming is a new CD release of solo piano works performed by John Martin, and later this year Parma will issue a double CD featuring McEncroe's Symphonic Suites No. 1 and 2). That dramatic career shift occurred when he began studying piano in earnest under Will Scarlet's direction and then Valerie Fawcett's and Helen Kennedy's after Scarlett's death; at the same time, an interest in composing also emerged, the formal study of which McEncroe undertook with Margaret Brandman in Sydney until 2012. It's the remarkable, just-released Dark Clouds In Life that is a primary concern of the composer at present, however, and it naturally figured heavily into the recent interview textura conducted with the composer (the textura review of the release is here).

1. Many a composer has created material that references heavy issues like death and suffering (works such as Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, Mahler's Sixth Symphony, Górecki's Symphony No. 3 (Symphony of Sorrowful Songs), and Berg's Violin Concerto come to mind), yet they often do so indirectly by dealing with the themes in universal terms. Natalie's Suite: Three Faces of Addiction, the three-movement work that opens Dark Clouds In Life, by comparison, resonates all the more powerfully for dealing in the most personal way imaginable with your own life experiences, specifically the struggles with addiction and depression that both you and your daughter have dealt with. What were some of the challenges you confronted in translating such experiences into musical form? And without wishing to be overly intrusive, have the two of you managed to successfully overcome those struggles or at least reached a point where they're under control?

Firstly, I'm often more moved by musical works that are dark in nature and colour. You mentioned one of my favourites, Gorecki's Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. There are others like Penderecki's Symphony No.7: Seven Gates Of Jerusalem, Rachmaninoff's Isle of The Dead, and Dvorak's Stabat Mater and his Requiem. There are so many more in this vein that I truly love. I generally like the sadder and darker music best and more often than not write in the minor key. I'm a positive and happy person by nature, but I just like the darker music best. If I write in a major key, you can expect a lot of melancholic major 7ths, minor 6ths, and half-diminished 7ths in there.

The big secret of this whole CD, including Natalie's Suite, is a statement of love for my daughter and an expression of deep concern for her welfare. I'm a sober alcoholic who joined AA thirty-three years ago and haven't looked back since. In all honesty I have no regrets; I had some great times in my drinking but in the end it all ground down to an absolute disaster. I didn't wake up one day thinking, “Oh, I'm an alcoholic and if I go to AA and all my problems will be over.” It was a slow, torturous, and confusing process, and the way back wasn't quick either. Suffice it to say it's the most rewarding thing I've ever done. My daughter's drug of choice and journey were different from mine, as is her journey back. She's been clear of drugs for a number of years now, but though the mental and emotional journey back is the longest and hardest part, she's getting there.

The first two movements of Natalie's Suite try to tap into the confusion, bewilderment, and frustrations that all people with similar problems have to face.

2. Of the many things about the recording that fascinate me, one I find particularly intriguing. In the release's liner notes, you describe the essence of addiction as being “the insanity of dong the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result” and that the strategy you adopted to illustrate this was to stay in the home key throughout Natalie's Suite. I find while listening to the work that an intense degree of pressure is generated when the material remains within that home key for its almost fifty-minute duration, a pressure that also might be associated with feelings of entrapment and even suffocation. Were you aiming to produce those kinds of impressions in the listener by setting the work in a single key?

The feelings you described regarding entrapment and suffocation are very perceptive of you. Perhaps I've been successful to convey that. Throw in utter confusion, too. That's exactly what I'm trying to get across.

3. The sequencing of material on a recording has a critical impact on its reception; to that end, I find the make-up of Dark Clouds In Life to be especially satisfying in that the large-scale symphonic pieces are followed by brief solo piano pieces (played by your piano teacher Helen Kennedy). What made you decide to sequence and design the recording's content in this way? And is there a particular tradition you feel Dark Clouds In Life is connected to, and are there composers you feel a particular affinity with?

I never think of other composers when I get a musical idea; I just collect them and over time add to and develop them. Certain fragments seem to want to group together; then themes and subject matters start to form in my head, which enables me to develop them into final works. I don't do commissions; I'm a retired chef who can indulge my passion and write what I want. My music takes ages to end up as finished works, and they meander through many processes before they get there. I only deal in my truth; I don't follow any trends. I've developed a great team of people around me, who I refer things to when I hit the ‘brick wall.' Only I know when something is finished and fits together, which in my case is a matter of trusting my musical instinct. My approach has never been academic, theoretical, or intellectual but emotional. They, my musical works, are more to me ‘musical images or musical paintings' that say something.

The more you get into music, the less you can have a favourite. There are just so many talented people out there and many who haven't had recognition. The scale of it simply keeps me humble and focused on just doing what I do. For me a recipe for insanity is to try to compare my efforts to those of others.

4. You've released two CDs of solo piano music (Reflections & Recollections, Volumes 1 and 2) and two featuring symphonic works (Affirmations and Aspirations and Dark Clouds In Life). Whereas many of the piano pieces are modest in duration, the opening movements of Natalie's Suite push past the twenty-minute mark and, if I'm not mistaken, are the longest recorded pieces of yours to date. Is it more difficult to write a movement of such length and achieve a sense of cohesiveness than when writing a shorter piano setting?

There are plenty of projects on the way at various stages of development. I have, however, written larger works, Symphonic Suites No.1 and 2, both of which are an hour each and will be released by Parma in September. Symphonic Suite No. 1 has seven movements and No. 2 six (both are at my YouTube channel movement by movement). Both have already been performed in Europe and upcoming performances are scheduled for The Czech Republic (Symphonic Suite No. 2), Bulgaria, and Munich (Symphonic Suite No. 1). Note, though, that the suites were an hour long each in their original form, but, as is often the case for composers, I had to cut sections out of the works to keep the likes of publishers, conductors, and orchestra management happy. But I'm sure that I'll use that lost material somewhere else.

5. Many an aspiring contemporary composer receives formal education in composition during his/her twenties and upon graduation confronts the challenges of establishing him/herself by having works performed and recorded. Your path to becoming a composer happened in a very different way as you worked for EMI Records, for much of that time as a label manager, during your early twenties and thirties and, though you did commence music studies with lessons in piano, trumpet, flute, and clarinet during that period, you didn't formally undertake the study of music theory and composition until 2003 when you were in your mid-fifties. How is it that this dramatic life change came about in your life when it did, and does the fact that composing arrived later than the norm imbue the creative work you're doing with a greater sense of urgency?

I do feel a little sense of urgency, but at the same time I feel every part of my journey has provided a rich tapestry of life to draw on. I'm now at a time when I can devote all my energies into getting my music written and into the world. Many others are not fortunate to be in this position. Although to reach the final conclusion is great, it's the journey that is the main event. If my music is liked and well-received (or not), to me it's not my business; that's out of my realm as I see it. What is important is whether I like it.

March 2017![]()