TEN QUESTIONS WITH GREGG BELISLE-CHI

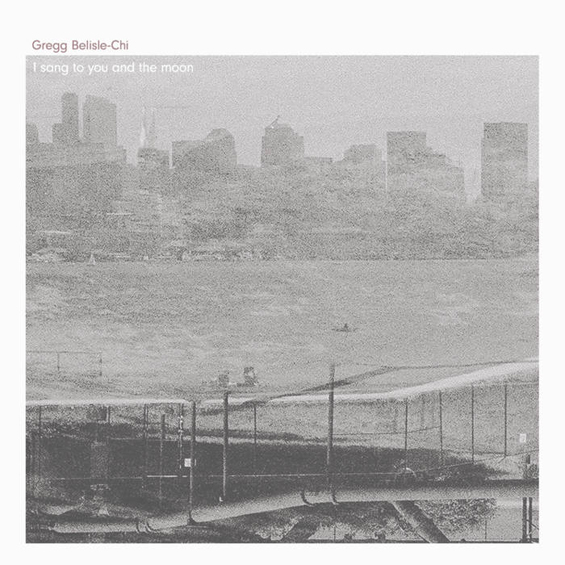

Originally based in Seattle and now ensconced in Brooklyn, New York, guitarist-composer Gregg Belisle-Chi brings a bold artistic sensibility to whatever project he tackles and playing situation he finds himself in. A graduate of the Cornish College of the Arts and the University of Washington's Music in Jazz and Improvised Music program, Belisle-Chi has studied and performed with an impressive array of artists, including Cuong Vu, Bill Frisell, Steve Swallow, Eyvind Kang, Wayne Horvitz, and Tom Varner, and is a member of Jim Knapp's Scrape Orchestra and Tyrant Lizard, to cite two outfits of many with which he's involved. Belisle-Chi is also forging a rather remarkable career as a solo artist with 2015's fine debut album, Tenebrae (Songlines), recently joined by the even more impressive I Sang to You and the Moon, a song-cycle based on the poetry of Carl Sandburg. textura spoke with Belisle-Chi recently about his new solo recording, mentors and influences, Tyrant Lizard, and other pressing matters.

1. First of all, I have to tell you how excited I was to discover that I Sang to You and the Moon features your guitar accompanied by trumpet (Ray Larsen), bass (Carmen Rothwell), and vocals (Chelsea Crabtree). Not that there's anything objectionable about it, but the guitar-bass-drums-and-keyboards (or sax) format is more common than one as refreshingly original as yours. How did your particular group concept come about?

The trio with Carmen and Ray, Tyrant Lizard, came about through a lot of common musical and compositional interests, but mostly because they're two of my closest friends and some of my favourite musicians from Seattle. So when I wrote the Moon music, which needed vocals (and who better than my wife, who's an exceptional vocalist), it just made sense to bring them into fold. I love the way they play and improvise, and we already communicate well. In that sense, it wasn't about creating an original sounding ensemble, though I'm happy you think it is, it was more about playing with people that I love.

2. You've just moved from Seattle to Brooklyn, a move that I imagine will have a profound impact on many levels. What prompted the decision and how will it affect the groups with which you're currently involved?

It's really just to learn from the people who are making the music that I'm interested in at the highest level. To be around these artists, some of who I've been listening to for a decade, is just really special and educational, and I'm so thankful to have the opportunity to do that now. I hope it won't affect my groups too much. Carmen moved here a few months ago; hopefully Ray can come out often. But I am excited to make music with new musicians on some new projects I'm working on.

3. There are commonalities between Tenebrae and the new one; both, for example, feature you accompanied by Crabtree, even if she appears on only three of the earlier album's tracks and more prominently on the new one. What in your estimation are the key differences between the two releases?

Honestly, I think this record is better; I feel like the writing and playing is better. I like that it's thematically cohesive, using all of Carl Sandburg's poetry. I feel like I musically grew a lot between the two records, and that had a lot to do with my education at the University of Washington's Masters program with Cuong Vu, Ted Poor, and Greg Sinibaldi ... especially Cuong. I do, however, like the sound of Tenebrae, which was all done to tape, and I just love the way it makes the guitar sound. Trevor Spencer did that record and was brilliant. Luke Bergman, who is a brilliant engineer and has the biggest ears ever, did the Moon record, but my budget at the time didn't allow for the luxury of tape.

4. The issue of influence looms large in most musicians' lives. I know some who do everything they can to avoid listening to certain musicians, especially ones with whom they share an instrument, for fear of being overly influenced; others embrace the opportunity to listen to and play with others, confident that doing so will ultimately foster the development of an individual voice. As you're someone who's played with Cuong Vu, Bill Frisell, Steve Swallow, Eyvind Kang, Wayne Horvitz, and others, what's your own position on the matter of influence?

That is so hard. I guess I go through both phases of listening and not listening to my heroes for precisely the reason you stated. I think on some level your influences will always seep through, or something of your musical past. But then there's someone like Wayne Krantz who really, consciously wiped away everything that remotely sounded like someone else, or at least what he interpreted as being someone else's; Cuong has done that too, to my ears. I'm not familiar with anyone who improvises like him; all I know is that is sounds so personal. That is so hard to do.

So, I guess I don't really know where I stand. I did go through a phase of not listening to any music at all to draw my influences from other art, like painters or poets, and try to draw musical ideas and conceptions from that. But then there's also the tradition of learning the language of Jazz which can, I think, only be done by listening and transcribing.

5. In the liner notes to the new release, Frisell is identified as a mentor. What specifically was entailed by that mentorship, and what are some of the more valuable things you took away from the association?

I met Bill in 2011 when we played together for a string of concerts in Jim Knapp's Scrape Orchestra, and we've maintained a friendship since then. He's such a positive influence and really cares about younger musicians. I think he really wants people to succeed and make cool art. He's also a really big guitar nerd, like me, so we really bond over that. But I think the most valuable thing I've learned from him isn't necessarily musical, it's his positivity and friendliness. He is just one of the nicest, most encouraging people I know and, at the end of the day, that's what I would love to be to someone else. So what better role model than Bill? Brian Blade and Ron Miles are also obnoxiously nice, and the three of them have a trio together. I can only imagine...

6. Given that both you and Ray Larsen play in each other's ensembles, what adjustments do you make when you're leading the project as opposed to when you're playing one of Ray's pieces in Tyrant Lizard? Do you bring a different mind-set to performing another person's material or do you bring a consistent sensibility to whatever playing situation you're in?

I think we're both good at giving the right amount of direction as well as the right amount of freedom to create. Ray is a really clear composer; I feel like I know how to get into his music with enough creative freedom to make something beautiful. So it's a balance. There were some rehearsals where I was probably too authoritarian with what I wanted and that can sometimes squelch enthusiasm and creativity, so I have to remind myself that what they're going to do naturally is probably better than what I could articulate. But, again, it's a balance. Sometimes we don't notice the details of a painting until someone points it out to us. So I try to be open to that as well.

7. I Sang to You and the Moon is a song-cycle based on the poetry of Carl Sandburg. What is it about his poetry that resonated with you so powerfully that you decided to build an entire album around it?

The first poem of his that I read was “White Shoulders,” which I had such a visceral reaction to. For whatever reason I couldn't stop thinking about Chelsea, my wife. So any art that really resonates with me at that level I decide to investigate further. I bought his entire collection and read through almost all of it and soon discovered that, out of the thousands of poems he wrote, only a handful seemed settable by my compositional skills. My friend Andy Clausen could probably compose an entire suite out of his works; I'm not there yet. So, I took the handful and decided to make a project out of it and was so happy with the result I decided it was worth recording.

8. How did you go about fashioning the music that accompanies Sandburg's texts, and how difficult was it to create music that would complement the writing?

Luckily the text is already there, so it's not like I had to do the singer-songwriter maneuvers of lyrics first then music, or music first then lyrics, or both at the same time, or some combination of all of them. I think the biggest thing for me is routine. I got up early every morning for several weeks and months and worked on the music. Something about routine really clarifies things for me. I feel like I got into a rhythm and exercised those muscles enough to where the heavy lifting soon became lighter.

Of course, you want the music to serve, or complement as you say, the writing. That has its own challenges. I don't know if I ‘succeeded' in that or not, but I did experiment with some ideas. For instance, “White Shoulders” seemed sort of like a palindrome to me, beginning and ending with “white shoulders.” So I composed the piece that way, sort of. It's not, by any means, a palindrome, but the theme at the beginning is the same at the end, just twisted a little, and the middle of the piece is built on static pitches with similar rhythms, with a melody on top, which I felt like the piece could ‘pivot' on, like how the middle of a palindrome is where the word or words pivots upon.

9. You're said to have an affinity for the music of György Ligeti as well as contemporary classical and chamber music. How did these particular interests develop? Did you grow up in a household filled with adventurous music or did these interests take serious hold during your studies at the Cornish College of the Arts and at the University of Washington, where you earned a Master's of Music in Jazz and Improvised Music?

I wasn't really digging into classical music, contemporary or otherwise, until after Cornish, where I did my undergrad. There, I was mostly listening to Jazz and Popular music. I played in a rock band called Tomten, played with a lot of singer-songwriters, and was trying to learn how to play Jazz. At the time I listened to Peter Bernstein and Kurt Rosenwinkel. I went through a big Ben Monder phase. All the guitar heroes. It wasn't until after I graduated that I seriously started investigating Beethoven, Bartok, Ligeti, Ives; a lot of that had to do with Cuong's influence. He really emphasized learning the musical lessons those masters provided and integrating that into your own music, whatever that was. I started studying with Cuong before UW and he really gave me a lot to listen to and think about before I began my studies. As far as my household influences go...that was all the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, music that I still love and enjoy.

10. I'm struck by your preference for putting the composition ahead of individual soloing, a quality also rare when for so many musicians personal expression is paramount. Where did this tendency towards self-effacement originate?

It was really to exercise my composition skills, because a few years ago I feel like I really lacked any. I didn't really write and all the pieces I did I felt were sort of weak or boring. So I just tried to commit to writing and make sure that what I did was really clear and articulate, the same way an improviser wants to be clear and articulate. Since finishing the Moon music, though, I've been focusing almost exclusively on improvising, both in a ‘free' and harmonically conventional context. I try to begin every practice session just improvising freely, and balancing that with learning bebop language like Charlie Parker or Sonny Rollins.

January 2017![]()