photo: Dana van Leeuwen / Decca

TEN QUESTIONS WITH HILARY HAHN

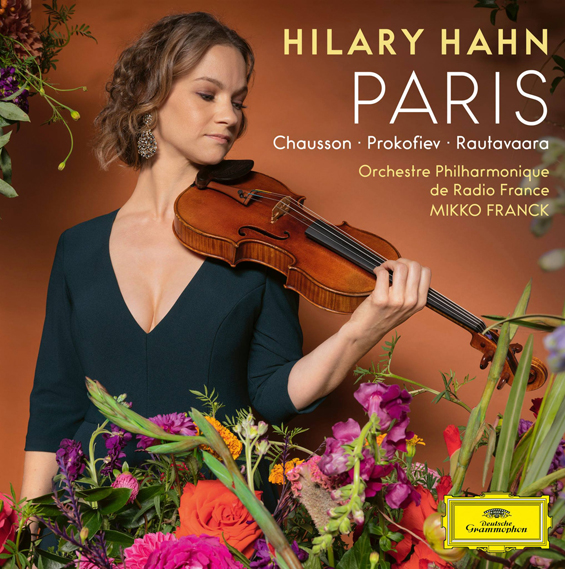

The release of Hilary Hahn's Paris, which features ravishing treatments of works by Ernest Chausson, Sergei Prokofiev, and Einojuhani Rautavaara, is merely the latest in a long and impressive string of accomplishments in the violinist's career. At seventeen, she made an incredible recording debut with Hilary Hahn Plays Bach, and in the decades since has issued numerous albums, three of which—her Brahms and Stravinsky concerto album (2003), her pairing of the Schoenberg and Sibelius concerti (2008), and her In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores (2013)—were awarded Grammys. Many a composer has written material especially for her, including Jennifer Higdon, whose Violin Concerto (which Hahn recorded with the Tchaikovsky concerto) won her the Pulitzer Prize, and Hahn has similarly become known for commissioning new works and supporting contemporary composers.

Enhancing her consummate technical ability and innate musicality is a restless desire to explore non-classical areas. In that spirit, she has collaborated on two records with the band …. And You Will Know Us By The Trail of Dead, partners with prepared-pianist Hauschka (Volker Bertelmann) in the free-improv duo Silfra, and connects regularly with fans through multiple online platforms. The “Postcards from the Road” feature at her site shares personal updates from travels around the world; she's also posted interviews with composers such as David Del Tredici, Du Yun, and others at her YouTube channel, a treasure trove of material about her music and the many projects with which she's involved. textura had the great pleasure of speaking with this singular artist on Feb. 26th, 2021 about the new release (reviewed here) and other performance-related matters.

1. I must start by asking how your life has been affected by the pandemic and how you've survived a year without travel or performances, things that have been fundamental to your life and career.

It's been a big learning process. I know my relationship to my work, but I've been thinking a lot about what it is to be an artist these days, and what it is to be in a field that communicates where communications are both shut down as far as in person is concerned and magnified as far as distance. During my sabbatical [ed. Hahn took a year-long sabbatical over the 2019-20 concert season and had planned to return to performing in September 2020], which overlapped six months with the beginning of the pandemic, I was looking at what other people were doing and was most affected by not being able to go to things. My experience of the arts at that point was fully up and running as an audience member. I was going to concerts, I had a subscription to the ballet, I was taking art classes and was doing all this stuff— really living the life of an artsgoer and arts lover—so I felt like I knew what it was like to be an audience member during this time. But right now I don't like looking at things in terms of silver linings; it's a terrible and tragic situation, and there's no if, ands, or buts about that.

One thing we can do now that can carry into the future is look at the newly developing digital connection space. It hasn't been conducive to the form of art that we want to experience, like synchronicity is a problem when you're trying to teach, and you can't play in an ensemble or rehearse over Zoom because there's a delay. But there are other things that are at the core of the arts, and there are ways to connect digitally. I've done a few world premieres digitally, which has been really fascinating for me as an artist, so there is a space in which these things can happen, and there can be a separate sort of genre of digitally connected performance that's maybe not 100% commercially produced but means something anyway. So that's the space that I've been really putting my time into exploring: what can we be doing right now that can still exist that once we're back on tour can still mean something and that can enhance the artistic experience for the audience and performer alike.

2. Let's talk about your wonderful new album Paris. Did you record it in 2019?

I recorded it during my artist residency with Radio France in the 2018-19 concert season; I think all of the sessions were in the second half of that season, but I was working with them on tour and was performing with them at festivals even starting in the summer. So the residency was with Radio France, and all the orchestral things I did in that residency were with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. So Paris definitely evolved out of collaboration and happened once the residency was scheduled and we started our summer festivals. We all felt that there was magic happening and thought about how we might capture it, so after we daydreamed our ideal album from this collaboration, we fit it in somehow. Even though the Philharmonique, conductor Mikko Franck, and I are all busy with different commitments, we managed in a matter of months to organize for a recording to happen.

3. And you have such a connection to the city.

A city like Paris has exclusivities, so you're normally not there more than once a year; because there's so much happening in the city, they want to make sure every concert has its own identity. So normally in the course of a season, I would be there once in a year, or if I was lucky maybe twice but at bookends of the season. In this case, being able to do an artist residency meant I was there four or five times and was touring with the orchestra. We'd start in Paris, and even if sometimes we wouldn't play there, we rehearsed there.

4. Did you stay in Paris for an extended time as part of the residency?

I've had the chance to live in different parts of the city for a week at a time, which is a wonderful experience, but for this residency it was a far commute so I stayed in the Radio France area. One thing I love about being a soloist is that I'm able to travel to different places, and for a few days I can both become part of the cultural fabric of the city but also be a tourist. I get to work with local musicians, who are extremely accomplished, and it does feel like I'm part of things for a short time. One of the things I appreciate about working in Paris is that for a short time I can kind of be part of whichever part of the city I'm performing in.

photo: Dana van Leeuwen / Decca

5. The album came together in a particularly fascinating way because Rautavaara's Deux Sérénades was really the piece that initiated its formation, and the story behind its creation is remarkable. What was your first impression of the piece, and how did it feel knowing that this was probably the last piece of music he created in his lifetime? And not only is that incredible, the piece was also a commission for you.

I think I have to tell a little bit of the origin of it for the feeling of that first play-through to resonate, but I will keep it short because it's like a relay story—so and so did this and then so and so did that and then this happened. Basically, after having worked on pieces by Rautavaara, I commissioned him to write a piece for my In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores project, and so I had premiered a work by him before and recorded one by him. I'd never met him in person, but I did communicate with him around that.

Mikko and Rautavaara met through the music and then became very close friends. And as he has presented pretty much every piece Rautavaara has written for orchestra, Mikko has become an interpretive ambassador of his music. When he invited me to play Rautavaara's Violin Concerto (1977) with him and the Philharmonique, it was an irreplaceable experience to learn it with someone who could tell me the composer's intentions and also translate them into a performance experience. So I kind of came at Rautavaara's music from that angle as well as being someone who was stepping into a momentum that already existed. In the course of that, I spoke with Mikko about sort of closing that circle by commissioning Rautavaara to write a piece for me and this orchestra. And that was the last I heard of it.

Though Mikko did speak with him, he thought that maybe he hadn't written the piece because of some, like, bureaucratic stuff that got in the way, and then Rautavaara passed away, and of course it was the loss of an icon, the loss of a great friend for Mikko, and a loss to the musical community. And I thought, “Oh, I wish I'd gotten to play another piece by him,” and Mikko thought, “Oh, there goes the piece that we talked about that will never come to existence,” and so we were mourning a lot of things at once. Then after the funeral, Mikko saw the manuscript in Rautavaara's study as presented by his widow.

It seemed as if somehow this piece was meant to be because one thing carried to another to another to another. The piece was completed according to Rautavaara's sketches by Kalevi Aho, who's a great Finnish composer in his own right and who was a student of Rautavaara's, and so that weight is in the entire manuscript when I have it in my hands. I remember just wanting to make the most of every note, like how can I be as expressive as possible, how can I bring all the emotion and convey the importance of this piece, and then I just kept not quite finding the groove on my own. But it can to me after I met with Mikko a few months before the rehearsals; we were both in Cologne at the same time and so got a rehearsal room for a day and spent all day talking about the piece. He showed me the moment in the score where Rautavaara's orchestration stopped—just like a vertical line of writing and then nothing—but as the sketch existed we knew what was supposed to come.

And that's when I started to develop a relationship to the violin part. As Mikko played the score on piano, I sort of sensed what it was and figured it out. And when we got with the orchestra for the first rehearsals, everyone felt that significance and was very earnest about every note. Mikko also showed us that a lot of the work extensively quotes one of Rautavaara's operas, and as I knew the aria I knew where accents fall on the words and the intention in the libretto.

What Mikko taught us is that instead of trying to make more out of the orchestration, you have to be in the moment and let it speak. In trying so hard to convey this music, in the end it's speaking its own statement, and we just have to be riding inside of the waves. That was a revelation, and the violin part, although it quotes from a singer and an aria, is not operatic. It's not supposed to be maximized and sung out, it's supposed to be held inside of it. As you're playing, you're singing, you're singing knowing your power and knowing your ability but choosing not to lean into all of it. And again, staying in that sort of hypnotic state where the music then can exist in its own space. So walking that line in the premiere was very powerful because you want to do something, but at the same time, the music needs to say its statement and needs to do its own job.

It was super powerful, and at the end of the premiere it felt really noticeable. I could feel that everyone knew that every note we played was one more note that wouldn't be new ever again. And when we played the final note, we knew it was the last new note from this composer's repertoire, and it almost felt like an end, a really profound end, but also a birth of something, because now his complete work that was meant to be played had been played and could now live. Until a piece is premiered it can't really live. It's meant to be a legacy, it's meant to be passed from one person to another, it's meant to be experienced between people. So our doing the premiere enabled that piece to enter the world, even though he was no longer with us in person, and at the end of the performance Mikko raised the manuscript to the heavens because it was so obvious there was no composer coming to take a bow. I hadn't premiered a piece posthumously before, but I knew that even though he himself was not physically present, his community was there, and as he was a spiritual person, I think Mikko holding the score up was really acknowledging his presence in the room.

6. Let's also talk about the other pieces. I'll confess I was a little surprised to discover you hadn't recorded Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No.1 before. Why did you wait until now to record it when it's such a staple of the repertoire?

It's a piece that's basically a trademark of mine. I think I could go five years without playing it and if someone calls me and says there's a concert tomorrow, can you do the Prokofiev piece, I'm like “Yep, I got it, I'm there,” because I love playing it, and it's also really a part of me. But it's been an evolution. I started it when I was in my teens and always loved it. It's such a dynamo, and there's nothing like it in the entire violin repertoire. It's mercurial and has all these different characters, and you can never just rest. He never lets you sit back, he's always keeping you very much in every note at the front of every note, and then when it changes, you have to change in the moment and be in it.

I had wanted to record it in the past, but it just never quite fit right, in the sense that maybe the collaboration was right but the programming wasn't or the setting around the recording sessions didn't feel quite right, or maybe it was exactly the right time but I didn't have a particular relationship with the colleagues that I would be able to record it with—I just kept waiting for the moment when it was obvious and compelling that it had to be done. These days I want to base my recordings on collaborations, really look at the artistic language that we're speaking and find the pieces that work in that, the things that are really fun, the things that couldn't be played the same way with another combination, different not better or worse, but that this is a unique thing that only happens between us in this piece. And let's capture that because that's a special magic that can't be planned.

I actually approached this with the attitude that when I'm in a situation where things are clicking I try to capture that, and that's why this record came together so quickly. So when we talked about doing the Rautavaara, which was the driving force behind making a big-scale record to make sure the piece reached everyone, and when Mikko and I started daydreaming about what else we could do, I said “Prokofiev one,” because for me for that work has always been Paris, and, in fact, it was premiered there in 1923. He was a deep part of the Parisian musical landscape at that time, so that was one, and then Chausson's Poème was chosen because I know how that orchestra plays, and I hadn't played Chausson with a French orchestra. And the way Mikko does architecture and details at the same time with his interpretations, I just knew we would get to a place with that piece that I couldn't get to in another way. So, I needed to explore that one as well, and he said, yes, we have a concert we can put Chausson in, no problem. So, there we had it.

7. It's a wonderful combination. They're all different, and they play to your strengths magnificently, the Prokofiev for all of the technical challenges and the various moods and terrain it encompasses, and then the others are so lyrical and expressive. When you're doing something that's been performed and recorded as much as the Prokofiev piece, do you steer clear of other people's interpretations or do you listen to them?

I listened to a lot when I was first learning the piece. I learned it as a student and at the time was taking in a lot of information. When you're a student you're trying to learn what your teacher's asking, you're trying to, you know, listen to all the recordings and you're not working with an orchestra necessarily all the time. And so you're working with a pianist and you hear your fellow students working on the piece. So there's a lot of input, and for me now I know my relationship to the piece.

I will listen to another recording if it's on the radio, but I don't seek it out. I think that I hear it as a different piece from how other people who have recorded it hear it; it's clear to me what that piece is, and no one is going to do that when they play it. I'm not averse to listening to others, I just don't feel like I'm seeking a redefinition for myself, and often when I'm learning music I will listen to the recordings, a lot before I start, then take a break from it, then check back in when I'm about to start taking it to the next level, and then check out, and then check back in. It's a little bit like, do I know the traditions, do I not have the traditions, what do I want to do, what do I not want to do, and then making sure I just kind of know what's out there.

photo: Dana van Leeuwen / Decca

8. Are there other violin concertos on your kind of ‘To Do' list? I'm thinking, for example, Berg's Violin Concerto would be one that's perfect for you.

I'm obsessed with the Ginastera Violin Concerto in the way that I was obsessed with the Schoenberg Violin Concerto. I had that feeling of I know what I want to do with this piece, I need to learn it, I need to perform it, I need to show people what I hear in it. That has only happened to me in such a visceral way with the Schoenberg, and that turned out pretty well, so I'm super-excited about the Ginastera, which I've been working on.

I was supposed to play it for the first time this season, so I'm trying to hold my horses a little bit and be patient and keep learning it so it's ready when it's time. It's an amazing, amazing work. It has different orchestration for every movement, it has little etudes, musical etudes on themes that come up later in the piece; it starts with a cadenza, it's tonal but not tonal—there's nothing else like it in the repertoire, and it's hardly ever played, I think because no one has really advocated for it and shown what it can be. There are some recordings out there, but when I look at the history of performance of that piece, it gets maybe one performance at a major orchestra and then nothing else; like the New York Philharmonic, it was written for them, and they performed the premiere in 1963 and have never done it since. So it's one of those pieces where I think the spark and ignition haven't lined up—someone has the spark but it doesn't catch, someone has the opportunity but the spark doesn't show up—so I feel like I need to do it. If someone says something is impossible, then I must do it. And as it's one of those pieces that seems impossible to play, I'm like, I'm going to learn how to play it.

9. As I watched the other day the video of your mesmerizing performance of The Lark Ascending (recorded in 2013 at the George Enescu Festival, with Camerata Salzburg and Louis Langrée conducting), I'm struck by the different experiences involved: on the one hand there are the viewers in the concert hall witnessing this music coming into being; on the other side are the performers giving it life. As I watch the video, I find myself wondering, “What is happening within her during this performance?”

That performance was part of a tour, and the orchestra and I were very, very connected; they were with me like glue, and that was really liberating. It required clarity of thought from me, because I can't just be glued to something and not know what shape I want it to be, and the orchestra also needs to pay attention to the soloist because of the way the piece starts. There has to be a sense of suspense and presence from everyone in the hall, the orchestra and the audience, in order for that delicacy of the ascending line and the cadenza to have its power. If you're just playing quiet notes in a row and there's no sense of tension and resolution in it, you're just playing notes, and it's like so much practicing. But the way you tie that line from the first moment, if everyone is is giving their full energy to the quiet notes and listening to them, when the piece grows it can really soar.

And I've gone through an evolution with The Lark Ascending as well because I used to try to be free with it, but I've realized that it really needs impulsiveness, impulsiveness to hold a note, to listen to your instinct and stay on it. But then if you get this internal nudge to push through things and you feel impulsive and want to move it, you've got to be able to do so, and then the tempo has to suit the moment. So for me that piece is very much going with the flow but also allowing it to not be just placid; it has to have that drive.

I also feel a little like you know if you're on a roller coaster, you feel gravity in the swoops, you feel like you're compressing and expanding, and you're also a little bit behind the motion with your body. And that piece, I feel like it swoops, and so I feel the compression and expansion within myself, which probably translates to my hands in some way. But, to me, the parallel with the bird is actually the physical sensation of turning, swooping, suspending, holding on the wind, riding, just like soaring but not soaring because you're high but soaring because you're supported and then, you know, having that total freedom of dimension. That's what I feel innately when I play the piece.

10. To finish, I don't know if you've seen this but The New York Times has this fascinating feature that's become quite popular. It's called “Five minutes that will make you love…,” such as five minutes that will make you love a soprano, a string quartet, what have you. What would you select if you were asked to contribute to an article titled “Five minutes that will make you love violin”?

I would maybe recommend five minutes from The Lark Ascending because it shows what violin can do, and it also has this lush orchestration that draws on the ensemble of violin with the group. Or maybe I'd put in something percussive like a Shostakovich or Prokofiev fast movement, or perhaps Pärt's Fratres or maybe five minutes of Bach, though that would maybe be more about Bach and less about the instrument.web site: HILARY HAHN

March 2021 ![]()