photo: Evan Shay

While the 2017 release of The Twilight Fall served notice that Chelsea McBride was a musician possessing considerable talent and ambition, her sophomore Socialist Night School effort, Aftermath (reviewed here), presents a remarkable realization of that debut's promise. Born and raised in Vancouver, the Toronto-based saxophonist, composer, and conductor leads her nineteen-member collective (herself included) through ten fully realized pieces on the new album, which repeatedly impresses for its stylistic breadth and the richness of its writing, arrangements, and performances. Socialist Night School isn't her only creative outlet, by the way: she also fronts the jazz trio Chelsea McBride Group and the jazz-pop sextet Chelsea and the Cityscape and performs regularly in Toronto when not playing elsewhere. She's been named one of Canada's top thirty-five jazz musicians under thirty-five by the CBC and was the first recipient of the Toronto Arts Foundation's Emerging Jazz Artist Award. With Aftermath just released, it seemed an ideal time to check in with her to discuss the new album, its themes, personal issues, and other things. textura is grateful to Chelsea for sharing her time and energy so generously with us in this interview.

TEN QUESTIONS WITH CHELSEA MCBRIDE

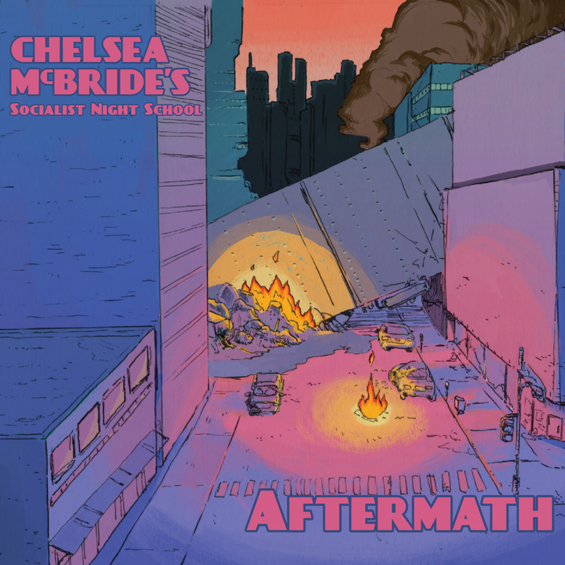

01. Aftermath is hardly a bleak album, but it does give the impression of being darker (for want of a better word) than its Socialist Night School predecessor, 2017's The Twilight Fall; even the cover image of Aftermath suggests this darker tone. If that's so, what's the reason for it?

This album really started from “Revolution Blues” and the conflict and division that I felt in the circumstances surrounding the 2016 US presidential election. I guess I grew up an optimist, and I've always believed we have the ability to get along and find common ground and consensus, even with people who aren't a lot like us. But in 2016 it felt like that wasn't possible anymore. It felt like we were losing sight of the fact that people on opposite ends of the political spectrum, or of different incomes, or of different races and religions, were still people.

I also, in the past few years of being an adult (including the process of putting out The Twilight Fall and seeing what came of it) have been seeing the effects of conflict and division in the microcosm of my life. Whether that was the dissolution of a long-term relationship, or friendships that grow and evolve and occasionally fall apart, or even navigating the professional world for the first time, I was beginning to take note of the butterfly effect in all the ways people were in conflict with each other. If you have relationships in which you can speak candidly—and bluntly, on occasion—with your friends, you're bound to run into a situation where you can't unsay something. And you can apologize and make amends and be better, but it doesn't change the fact that you hurt that person.

I don't think I was an optimist about this feeling when I first locked myself away in the Banff Centre to write this album. I was really digging back into the baggage of my past relationships, to see what went wrong and what was my fault and what wasn't. But that process teaches you a lot about the ways in which you have and haven't grown, and I honestly have come out the other side a better person from all these struggles. I'm better equipped to be an adult after making this album, which is a nice side benefit!

02. Without wishing to suggest that the writing on the earlier album was lacking (it wasn't), the new one, to these ears at least, shows growth in your writing; perhaps another way to put it is that the new material—I'm thinking, for example, of “Niagara,” “Love is on the Line,” and “Say You Love Me,” each of them deeply affecting and emotionally resonant—indicates your writing has matured since the last album. Does that strike you as an accurate assessment?

I mean, I'm not even thirty yet—of course my writing is going to grow and evolve! I'm still finding my voice. This album was particularly fun and challenging, though, because I actually wrote it away from all my mentors. I broke more than a few writing rules throughout the course of the album's creation, and I'm definitely toeing the line of professional over-sharing (see tracks seven and eight). But I felt like it was time for me to test the boundaries of what I could do, whether that was low voicings on the trombone section, or putting a two-song spotlight on mental health (and a one-song-each spotlight on politics and religion). I was told as a kid that you don't talk about some of these things, but these are the big fundamental questions that you wrestle with as you grow up, whether you're fifteen or fifty or ninety. It doesn't make sense to me to hide this subject matter away.

Regarding the tunes you've highlighted, I spent a lot of time trying to balance elements, in my writing and in the rehearsal process (and of course, later in mixing, with the help of Kevin Stolz and Jeremy Darby [and Julian Decorte's impressive editing skills]). I was aiming for an intensity of feeling, yes, but I also wanted to do it with only the most necessary voices. So that's why you hear the ensemble drop out for large portions in those tunes and give way to some of the softer instruments, or why you hear repeated motifs over and over again. It was a bit of an exercise in being concise, and simple, and sticking only to the most basic elements.

03. There's a seamless carry-over from The Twilight Fall to Aftermath because of the consistency of the personnel and your writing and arrangements. But one noticeable difference is the ratio of vocal-to-instrumental tracks, with the earlier one more evenly split and the new one featuring vocals on nine of the ten pieces. What accounts for this shift in vocal emphasis?

I'm the daughter of a radio broadcaster. Music with words has always been a big part of what influences me, and I started writing songs with lyrics, not without. The Twilight Fall was the first project I undertook with the Socialists after I finished my Humber degree, and so elements of jazz school are heard throughout. But I often write music with words and then delete them later, so initially, this album had all tracks with words. But there's a reason “The Righteous and the Wicked” does not have lyrics now—and even the band hasn't seen them. They were bad, in my opinion, but more importantly, the song didn't need them.

I think in future projects I would probably do a vocal/instrumental split that is closer to The Twilight Fall, but for this project it felt right to have Alex literally tell the story of some of these songs. And it was a good chance for me to practice the craft of working lyrics and a vocalist into the texture of the rest of the big band.

04. In the pre-recording stages, what's the most difficult part of the process for you (and why)—arranging, composing, lyrics?

There's a middle stage that happens in the composition of every tune. Sometimes it happens at the beginning, but I'm both lucky and not: it usually happens in the middle. I'll have a great idea, the first minute of a tune will just spill out, and then I will hit a wall and be confronted with all of that self-doubt. Even if I'm excited about the idea, it won't have a clear destination or resolution, and I'll be stuck trying to mathematically figure out how to get around, over, or through that wall.

I am so thankful for the time I had at the Banff Centre because it taught me a lot about navigating that wall. In my real life, so to speak, I don't have the time to sit there and hang out in creative purgatory until the answer springs from the darkness: I have to teach, or go to a gig, or call my mom—something will come up. But when I was at the Banff Centre, I was able to sit in that space and try stuff, with no pressure. I could try every possible chord until one or two of them felt right, I could transpose things, I could sit at the piano and try different combinations of notes. Or I could go get food, or hang out in the mountains, or hike. I had all the space in the world to either dive into the discomfort, or leave it and distract myself.

I don't really struggle with just lyrics, or just orchestration; each piece poses its own specific challenge. I guess form is a recurring one (as are words), and instrumentation was certainly a big challenge on this album, as I have so many woodwinds. But each piece had its own roadblock—“Righteous” began with the first two bars but nothing else, and “Love Is On The Line” started from the end, but I had to move it around in order to suit the band and Alex's voice. “Say You Love Me” was one of the rare ones where every section, I had to stop and work out what came next, especially with regards to the instrumentation. And because I was trying to make these songs work together, there were some unique issues: I had to change the key in “Say You Love Me” to work with “Revolution Blues,” and “Fly By Night” and “Niagara” needed to end up in keys that worked together as well, even though they didn't necessarily start there. I guess it's easier to say that when one element comes easily, another one is going to present the challenge—and arranging and orchestrating these pieces is just a balancing act. It's all about making elements work together.

05. The personnel is almost the same on the new album as it was on the Socialist Night School debut, which wouldn't normally be all that significant but in this case is when the size of the band is nineteen musicians, including yourself. How difficult was it to reconvene almost all of the same musicians for the second recording?

Actually, I've been talking about it since just after the last recording, so it wasn't hard to convince anybody to sign up for this one! It was a bit of a scheduling shuffle, especially as I balanced grant deadlines and results with my personal life, which has been a little topsy-turvy for the past few years. But everybody wanted to do it. We've all grown into a weird little family, and we all genuinely like spending time together. And everybody's really poured their hearts into the making of this recording and the stories of the songs, and ... that's not something I can ask for as a leader, that's only something my musicians can give.

A lot of people say they have the best band ever, but I know it to be true. It hasn't always been easy to tell these stories or make the recordings, but everybody wants to be there and be a part of these crazy projects I'm leading. It's such a privilege and an honour to work with people who are that invested; I'm honestly so lucky to be able to do this.

06. The album was recorded in a mere three days in April of this year, which seems noteworthy given the amount of material recorded and the complexity of the arrangements. How challenging was it to lay down the material in such a short amount of time?

I mean, we went into the studio after a few rehearsals, and that was a huge help. But it was tough! We made a few calls on the fly to make it easier to record; we recorded the woodwind doubles separately, and a lot of the vocals, and we made sure to take frequent short breaks to keep everybody fresh. We also are always listening to what everybody in the band has to say—if they're fatigued, if they're having trouble hearing, if they're questioning something—and do our best to address all of that in the fastest, clearest way possible.

My producer Kevin and I have a really good system going (this is now our third album working together as producer and bandleader), and he's listening for things that I can't necessarily pay attention to on the floor, like my own playing or the ensemble under my solos. If one of us isn't sure that something is working, we do it again, the same if a band member pipes up to say “I totally missed this.” But we make a point of moving as quickly and efficiently as possible, and making sure that in the process we get everybody's best takes and that everybody has what they need to play their best. Hence the frequent breaks; when we're on, we're on—but you can't do that all day. Sometimes, you also need to turn off!

07. Stylistically, some unexpected moments emerge on the album. The rhythm driving “The Righteous and the Wicked” suggests a drum'n'bass influence, for instance, whereas the flamboyance and theatricality of “House On Fire” gives it a rather Weill-Brecht character. When you're composing material for an album, are you deliberately weaving different flavours into the writing or do they emerge of their own accord?

I grew up listening to everything. And what I didn't listen to, I learned in music lessons; I came across jazz and big band in high school, and it's always been one of my favourite formats to play in and write for, in any capacity. But I also studied piano and voice (and later saxophone) and learned that good music is just good music--it doesn't matter what genre it is. I, like many musically inclined teenagers, had a metal phase, and I grew up listening to electronic music, and pop-punk, and country, and boy bands, along with jazz, and Broadway. I was always drawn to music with a good melody, and musical theatre was a natural fit for that. But I also love music with a relentless groove, and I find it a challenge to write--so when I write specific grooves, I'm really trying to make it perfect. I have this incredible rhythm section that has as diverse a set of influences as I do, so when I ask them to play the ridiculous or the mundane or the relentlessly cheesy, they can do it. And having a rhythm section that can play all those genres somewhat authentically gives me a bigger palette to work with, which is so much fun.

And I have to add: one of the compositional ideas that I've grown into is that whatever you write, it should just be true to the intention of the piece. That whole philosophy solidified while I wrote this album: “Revolution Blues” was an angsty protest song, so I was going to make it angsty and protest-y. “Love Is On The Line” is one of those tender love songs, so it needed to push all the right buttons. And “House On Fire” is about the ridiculousness of capitalism—what better way to tell that story than through a circus waltz that belongs in a musical?

08. A press note accompanying the album indicates that “Fly By Night” and “Niagara” are related to your experience with mental illness. Could you elaborate on what issues you were dealing with and how that translated into the compositions?

What issues I continue to deal with, honestly. I'm bipolar and I have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (which has both a physical and mental health component, hurrah!), and I try to be open about it without hitting people over the head with it (a difficult balance, I'm learning, especially given that over-sharing and mania are just parts of this disorder). I do usually think of myself as “recovered” from both of these things, or “in remission,” but it's not that my disorder has disappeared or ever will; it's just treated.

Coping with mental illness in any form is obviously a huge challenge on its own. Coping with two is harder. And trying to cope while also trying to appear “normal” enough to be hirable, or likable, and also pass all my classes and function at my job ... that felt impossible. It still does, sometimes. This diagnosis has caused me to lose friends and get kicked out of bands and it's made a ton of people uncomfortable, but I don't get to close this tab or stop speaking to myself to get away from it, because it lives in my brain.

When I wrote these two pieces, I was actually pretty stable. I still am, which given the process of making a record about conflict in very stressful circumstances, is nothing short of a small miracle. But I wanted to give other people a temporary but important look at what life was like inside of my brain. It wasn't going to change the gigs I lost or the friends I might have had, and it wasn't going to take back anything I said that I shouldn't have. But it would at least be a chance to try and bridge the gap between myself and a neurotypical person, to see if they could experience the world the same way I did.

Bipolar disorder isn't super common. It takes a long time to get diagnosed and treated properly, and it can be incredibly destructive. Pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder is under-diagnosed, and a lot of women who could have it aren't aware of it at all. I certainly wasn't knowledgeable about either of these conditions until I had them. And the frank truth is: it sucks having this. But I have an incredible support network: a loving and supportive family scattered around the continent, a small but essential crew of friends who I can turn to for anything, a very understanding professional network (in varying degrees of detail), a couple of therapists I could call if I needed (who I used to see often), and an amazing family doctor and pharmacist. And I've developed habits over the past few years that keep me really healthy, physically and mentally. It's a huge process to recover and manage my brain, even after all these years, and that's a difficult concept to comprehend if you've never done it yourself. I thought it made sense, on an album about conflict, to deal with the issue that really has defined at least the first half of my twenties: the conflict I had with my own mind.

I do really want to add, after talking about all this super heavy stuff: if you suspect that mental illness, or even just some temporary, totally-normal grieving, is getting the bettter of you, there are resources available. The Canadian Mental Health Association is a great place to start, and if you don't feel you can make the call yourself, enlist a friend or family member, or your doctor. Talking about all this is a huge part of beating the stigma. I've been talking about my mental health and self-care practices on my social media for a long time, and it felt like a natural move to include this on the album. It won't make me the most popular musician ever, but at least I'm being honest about who I am.

09. Among the many things that are striking about the album is the track sequencing, which I think works splendidly to its advantage. How critical an aspect of the process was that for Aftermath in your eyes?

This album arguably started with the sequence! I wrote “Revolution Blues” and knew it'd be the opener. Then I started sketching the other pieces, and once I decided that “Love Is On The Line” belonged to the Socialists and not my other band, I knew it was the right note to end on. I played around with a few different options for the middle tracks, and as the songs took shape it became clearer which key changes and which sequence was going to work best. And I really did get picky—starting notes and keys were a factor, instrumentation was a factor, mood was a factor, subject matter was a factor (the two space tunes are separated, as are the love songs); there were only a few sequences that would have worked, and I tested them all, and eventually settled on the one you hear.

If you're a little intimidated about diving into a whole album about conflict, this album actually works great in two halves: listen to “Revolution Blues” to “House On Fire” and then come back for “The Void Becomes You” to “Love Is On The Line.” But if you have an hour and fifteen minutes, listen top to bottom, and hear the evolution from that initial feeling of angst and alienation to love, and acceptance, and personal growth. If clouds have silver linings and storms clear to sunshine, well, you'll grow through what you go through too. I did, and I still do. That's just part of being human.

10. I'm guessing that, in spite of the album's supposedly darker tone, you don't want listeners to be deflated by Aftermath. What kind of response would you most like to see listeners have after listening to it?

I actually was kind of hoping this would be a depressing record! But I guess I'm just not that depressed a person anymore, which I'm obviously pretty happy about.

I want listeners to come away with a changed understanding of their actions. There is so much in others' journeys that you just don't see or hear about or understand, and it's really easy to not be kind to others, especially in a world that can be so divided. But once you start to realize that that's somebody's kid, that that's somebody who just lost their job or somebody who's working hard to help their kid get to a better place, even if you have some form of conflict to resolve, you can try and do it in a way that works for everyone. We could all—myself included—benefit from trying to be better people.

website: CHELSEA MCBRIDE

November 2019![]()